Give the backdrop of the last few blog posts, I thought it would be interesting to engage one of my fellow lobbyists from Washington State University about his opinions on the ever expanding Belt and Road Initiative coming out of China. We talked at length about the widespread scope of the infrastructure project, as well as the impacts that it may have on international marketplaces in both short term and long term impacts.

The Belt and Road Initiative is a part of China’s plan to become the dominant global superpower by 2050, through infrastructure investments across the planet, incorporating concepts like network and financial development for sovereign states cresting into the first world standing.

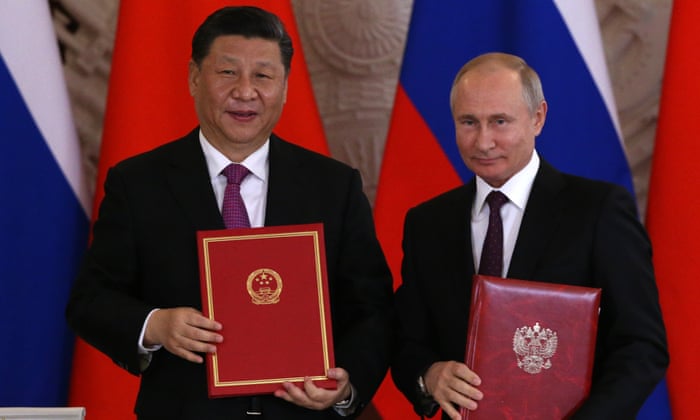

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 4.0 Photo by Owennson.

Question: What do you think are the short term impacts of China’s Belt and Road initiative on the socioeconomic power rankings globally?

MJ: It’s a more of a long game that they’re playing, where the short term impacts are founded in countries becoming more skeptical about China’s influence in military and economic position, but the countries won’t stop China’s expansion because of lack of progress in effective intellectual property controls via failed trade projects in the Eurasia region. The China perspectives that countries in the West hold try to focus on being more independent of China in an attempt to beat them, instead of cooperate with them, which leads to diplomatic quagmires.

Question: If the Belt & Road Initiative succeeds in its long term goals, what effects do you think it will it have on markets in terms of currency dominance?

MJ: Currently, the United States Dollar (USD) is the dominant currency in global trade, due to the high level of international and economic influence, but that has become more and more threatened by poorly executed state efforts, such as the Iran deal. The downside is that China has the benefit of being able to manipulate their currency as much as they want, which allows them more freedom in economic control. If their plan succeeds they will establish themselves as an international superpower, their economic influence will trickle into their trading partners, allowing them to control market forces. Their market controls could hamper the economic freedoms of surrounding countries and limit market engagement with non-trading countries and sovereign states.

Question: If you were going to give advice to state diplomats on engaging China to promote long term diplomatic success, what would you tell them?

MJ: I would tell them that their is probably a lot of value not trying China’s industries from growing by trying to regulate them, such as the United States trying to hamper telecommunications companies, and to avoid trying to build wonky provision based trade deals that try to limit growth in industry. The focus of the solution should be towards working with allies who are trading with them to limit the spread of the initiative’s influence internationally.

I want to thank Mitchell for his time and support of this work, as he provided a lot of insights to me about the dynamic pressure that China is beginning to put onto global markets and how that changes them. If U.S. State efforts don’t become more sophisticated quickly, it could lead to a failure in securing long term geopolitical and economic power positions for the United States.